What makes this field interesting is that it was the location of one of the early conflicts of the Civil War, and while the conflict actually took place as a running street battle down Lindell and Olive Blvds after the Confederate Camp surrendered, we know with certainty that the encampment itself was located fairly precisely in this field. But to back up a bit.

At the outset of the Civil War, the Governor of Missouri, Claiborne Fox Jackson, displayed clear leanings towards the Confederacy but the Constitutional Convention of the state voted against secession. In an effort to forcibly shift the tide in the State, Jackson and his Confederate allies concocted a plan to capture St. Louis. To do this, Jackson and his allies would need to capture the St. Louis Arsenal, which at the time was the depot for weapons for the entire Western theater and was heavily defending with earthworks and a significant military presence.

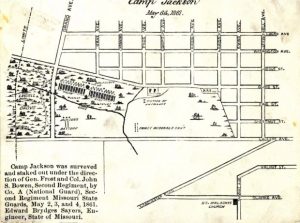

Around May 1 Jackson sent Daniel Frost and several groups of Missouri Militia (mostly from the St. Louis area) to create an encampment at Lindell Grove, which was at the corner of Lindell and Grand.

At the same time, Jackson petitioned Jefferson Davis for artillery support in order to attack the walls of the Arsenal. The artillery and additional weapons were sent up the Mississippi, and were apparently picked up at the riverfront by members of the Missouri Militia and brought to Camp Jackson, as the encampment was called.

Nathaniel Lyon, commander of the Union forces in St. Louis, immediately began preparations for an attack on the Arsenal, but also gathered Union militia and permanent Union soldiers at Jefferson Barracks and the Arsenal. This army marched out of the Arsenal on May 10 with the intent of clearing the encampment and arresting those encamped. Frost surrendered and those encamped were arrested and marched down Olive towards the Arsenal. However, Confederate and Union sympathizers seemed to have thrown things at both sides, which ultimately led to gunfire and a running battle on the streets of the city. Several bystanders were killed in the conflict, and because of fears of reprisals by both sides (including the fear that German immigrants would rise up against native-born Americans), martial law was declared in the city. Notable witnesses to the street battle included William T. Sherman, who, at the time, had not re-entered service in the Union army.

Jackson went on to lead the Confederate supporters in Missouri, and formally appointed Sterling Price General of the Confederates in Missouri. Price would later lead several armies that tried to gain control of St. Louis, but he was never able to take the city or the Arsenal. This proved to be a significant failure for the Confederacy, as the Arsenal was a major supply point for Grant’s armies as they advanced down the Mississippi. Lyon was later killed in battle at Wilson’s Creek, after a campaign he pursued the armies of Sterling Price through central Missouri.

The encampment itself was spread out across the south east corner of Grand and Lindell, with several units of militia assigned various areas. The total number of troops in the encampment numbered close to 800. What is interesting to note in the image above is that the encampment is situated just north of Mill Creek, which was likely used a water supply and waste disposal for the camp. This photo of the encampment is a bit confusing and it is unclear what orientation this might be, and whether we are looking at Missouri Militia or Union militia after the camp broke up (I will have to consult with local scholars on this point).

If I had to bet, though, I would think this is looking south from north of Lindell, and that the street running through the middle of the image may very well be Lindell. If thats the case, the encampment is located in the far tree line. I have not seen this photo in great detail, so I can’t make out anything on the troops parading in the foreground.

Archaeologically, I suspect that we will not find much if anything from the Civil War era. However, here is what I DO know: an encampment of 800 soldiers at a given spot for around three to four weeks would create a great deal of trash and waste. That waste would have been disposed locally, perhaps in the creek, perhaps burned, or perhaps just thrown in the forest. Further, there are areas in these fields where there were never significant buildings, in other words buildings with foundations. Most of the buildings on Pine were residential with front and back yards, and when they were demolished, they were replaced with parking lots. The paving for the parking lots were removed when the area was turned to grass for the University. Hence, and this is a HUGE leap of faith, if anything were to survive from the encampment, it would be located in those areas that were back and front yards of those houses.

Again, its a huge guess. With the new University research building going in that field, this will be the lat opportunity to explore this site to see if there are any remains from the Civil War. At the same time, we DO know there are remains of other buildings in that field, and some of those houses date to immediately after the Civil War, and we actually have a great deal of demographic information about the people who lived on that block. More on that later.